What does Mexico City has in common with cities like Turin, Seoul, Helsinki, Cape Town or Taipei? All have been named World Design Capital. Anything else? Let's do a little exercise: imagine the best conditions of what was once the Distrito Federal, remember its best areas, review its best projects of urban and social design, and respond based on the first impression: is it a well designed city?

The meaning of wide judgments, such as “good” –or “bad”– is as relative as the implications of a general name such as “World Design Capital”. The truth is that there is a big distance between Mexico City and Seoul that stands beyond the imaginary.

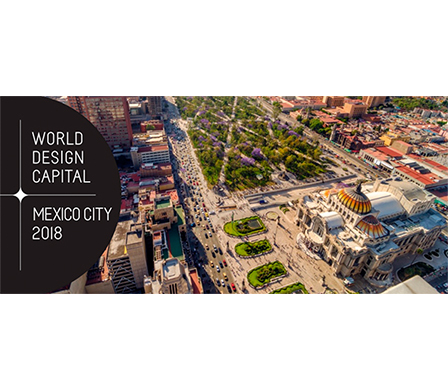

On October 29, 2015, the International Council of Societies of Industrial Design (ICSID) designated Mexico City as the 2018 World Design Capital. More than a year after the news broke, and in the midst of unfortunate government projects, such as the Corridor Cultural Chapultepec or the Centro de Transferencia Modal (CETRAM) in the same area, the title continues to be questioned. Yes, the capital, as a good centralized territory, enjoys an interesting design scene. "Vibrant," it is said. But there is a long way to go to be a model.

It is not fortuitous that the appointment comes in the days of Miguel Angel Mancera, who has been determined to transform the capital into a brand city, such as New York or Paris. The new CDMX logo and advertising strategies around the new name are just a few examples of the political uses of design. For its part, both the title and the paraphernalia around the World Design Capital recalls the absurd stubborness of considering Mexico City as the "New Berlin", which, judging by a couple of texts[1], seems to be held in a bubble where there are a number of art galleries, museums and trendy restaurants.

It seems that the same thing happens in terms of design. No, we are not Berlin, not Turin, Helsinki, or Seoul. According to ICSID, the designation of World Design Capital "is awarded every two years to [different] cities based on their commitment to use design as an effective tool for social, economic and cultural development." Let's go back to the initial exercise, what design projects come to mind in this context? It is not enough having colored structures, arranged without any sense on the sidewalk, to park your bicycle. Neither are the zebra steps with the figure of a dog suggesting an "inclusive" design, or LED lighting around a pedestrian circuit to "favor" the night view of the runners.

The ICSID adds: "Mexico City will serve as a model for other megacities around the world that face challenges of urbanization and that use design thinking to ensure a safer and more livable city. Beyond the extreme inequality that runs between central and peripheral colonies, at ground level or underground, problems of violence and insecurity, terrible traffic, pollution... Is design beyond all that? Or what design makes Mexico City a "model" and is used to make the "city safer and more habitable"?

Other perspectives are possible. The appointment is useful to think about the implications and discuss the challenges and possibilities of designers in such a complex context, but also to celebrate the diversity of local design. Facing the situation, Mario Ballesteros, director of Archivo Diseño y Arquitectura, raises a series of questions with the exhibition México Ciudad Diseño, which far from approaching the territory as a brand, anlyzes different moments of design as a discipline and a tool with the power to generate changes: "What makes a design capital? What implications does this nomination have for an overcrowded urban agglomeration [...]? How can we, through design, shorten the tremendous gaps that persist in all areas of our daily lives? "

From the approaches and the proposal of the exhibition, other questions arise from this flank: Can Mexico City be a design capital? For Mario Ballesteros the questions are: "What can Mexico City offer in terms of design culture? What makes us different from other global creative cities? To what extent is our production better, worse, or different from what is produced elsewhere? And one more, how can you consolidate design as a tool of positive change for the inhabitants of this city, even for those who have no specific interest in design?

On the other hand, Cecilia León de la Barra, from her perspective as a designer and critic, believes that the nomination will allow "people to see, talk, learn or demand design". The title's character, however, can not be left: "It's between marketing and business. But in the end, we must take advantage of its benefits. If we can host the Olympic Games or the World Cup, we can be the [World Design] Capital. There is already design, it is already a capital". In another context, beyond the program of activities of the project, for Ballesteros "what is interesting is what represents 2018 as a conjuncture. 50 years after the Olympic Games and Tlatelolco, in an election year, which is sure to be politically convulsive, 2018 will be an interesting moment to see what design can do for us as a city, society and culture."

It is time to overcome the ideals of decoration, to bet on the power of form. A rebellious design is needed in Mexico. "It will be fundamental that design (and designers) come out of its bubble, shake off its superficiality and elitism, embrace the street, approach non-designers, to the millions of people for whom design is not a blessing, a pleasure that can be given or a luxury, but a burden among many others because it is insufficient or deficient. Bad design affects us as much or more as good design. And in this city, the most basic design problems (infrastructure, transportation, accessibility, health, housing, etc.) are the order of the day".

While designers have shaped the world with their vision, its power as a tool is a continual rethinking. And that is, perhaps, the opportunity that brings the title of Design Capital. For León de la Barra, "Mexico City has its own requirements: it has a terrible traffic theme, but it is also present in other cities. It does not mean that it is the only one and it is badly designed. Design does not save the world, but it can improve these problems”. However, she adds that designers also have a role as citizens,"it is a social question, of how the human being, the individual or the citizen first observes, analyzes the problem and then proposes changes. They are small acts that try to make improvements. "

The subject of education is drawn between answers. It is not surprising. It is inevitable if we think that schools are responsible for training the professionals of the future, who will not only create beautiful objects but will have to make a commitment to their environment. The power of design is largely associated with its role: "[that power] depends on the focus and weight given to the notion of design. If we stay with the traditional definition of school, design as a stylist or 'author signature', its power and relevance to deal with the challenges ahead, as a city, would be absolutely despicable. "

As an academic, León de la Barra believes that there is a theme of education that is fragmented: "In classes, sometimes we focus on doing things more than solving social problems. Inside the classroom is very difficult to live them, you have to go outside and observe. It is not bad that in school we teach how to create objects or things that seem superficial, it is a warm-up to contribute later with something much bigger. Communication between areas is another matter: if the student does not know that there is a social problem, how will he solve it?"

So far, the title of Mexico City as the World Design Capital has at least put up to discussion a topic that is necessary and urgent in Mexico: the social responsibility of design. Faced with a collaboration between designers and the government, Mario Ballesteros and Cecilia León de la Barra agree: although efforts have been made, more communication between the two sectors is needed to achieve a common good.

México Ciudad Diseño also proposes a reading that covers the past and the present of local design. Ballesteros points out that it is necessary "an open, critical and informed view. It is fundamental to know the history of the profession, specially the broad and material culture of design, to learn to question it and to have a (self) critical stance". For León de la Barra," designers must appropriate tradition and not intend to go back or repeat the clichés of the past. It's about going forward to take ownership of yourself plus the one next door. "

Design has a long tradition in Mexico and its present looks promising. The discipline has been projected in our territory in its broadest expression: industrial or graphic design, for example, enjoy a good momentum. Not to mention architecture, which also responds to problem solving. In all three areas, architects or designers from different generations have given Mexico City an important symbolic value. To review them in these lines does not grant justice as it seeks to do México Ciudad Diseño, which turns the idea of "Design Capital" to show and highlight the projects that are given in this geography, understanding design not as a final object, but as a process that has an impact in all areas of everyday life.

In times like these, the title is a excuse to dialogue and analyze what design needs. Less speech, more action. The current state of the city requires it.